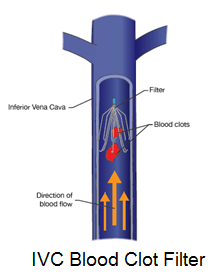

Lawyers for both IVC filter plaintiffs and IVC filter manufacturers continue to tussle in court over the FDA’s role in allowing different IVC filters to be sold on the market. Defense lawyers would like juries to believe that IVC filters were approved by the FDA for implanting in people’s inferior vena cava. Plaintiff’s lawyers want juries to know that IVC filters were never approved by the FDA for use in people. Can both sides be right? What gives? IVC filter makers face liability over a little-known but common FDA process.

Lawyers for both IVC filter plaintiffs and IVC filter manufacturers continue to tussle in court over the FDA’s role in allowing different IVC filters to be sold on the market. Defense lawyers would like juries to believe that IVC filters were approved by the FDA for implanting in people’s inferior vena cava. Plaintiff’s lawyers want juries to know that IVC filters were never approved by the FDA for use in people. Can both sides be right? What gives? IVC filter makers face liability over a little-known but common FDA process.Federal Preemption for Medical Devices

The makers of medical devices which have been approved by the FDA through its regular Pre-market Approval (PMA) process typically avoid lawsuits against those products. That vanishing liability is a a direct result of a 1970s act that changed the nation’s long-established tort law. Federal regulatory preemption of medical devices began with the 1976 Medical Device Amendments (MDA) to the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (FDCA). 21 U.S.C. §§ 360c-1; 21 U.S.C. §§ 301 et seq.

Related: IVC Filter Lawsuit | Lawyer

In a nutshell, the 1976 Act means that any medical device approved by the FDA through its PMA process immunizes its maker against legal liability. Whether or not the device turns out to hurt more people than it helps doesn’t matter. If the FDA approved it, people injured by such a device are out of luck. They had, and still have, little to no chance to remedy their grievances in court.

IVC Filters Not Approved by FDA

IVC filters, by contrast, have not been approved by the FDA. They never went through the agency’s PMA process. Instead, IVC filters have been “cleared” by the FDA under the auspices of the agency’s 510(k) clearance process. This process greatly abbreviates the PMA path. It allows the agency to “clear” devices for the market without putting them through the rigorous testing required of devices which seek full FDA approval.

The FDA web site explains, “A 510(k) is a premarket submission made to FDA to demonstrate that the device to be marketed is at least as safe and effective, that is, substantially equivalent, to a legally marketed device (21 CFR 807.92(a)(3)) that is not subject to PMA.” The term “substantially equivalent” can, of course, be very subjective.

Because devices “cleared” through 510(k) are not subject to the same rigorous testing as products put through the PMA process, the companies that make them can still be subject to civil liability.

In the first IVC filter trial in the Phoenix MDL court against C.R. Bard last month, the plaintiff’s attorneys sought to keep misleading characterizations of the FDA’s device approval processes from coming before the jury. They felt that any mention of the FDA allowing the filter on the market could prejudice the jury. The Arizona federal judge overseeing the case denied the plaintiff’s motion to preclude evidence about the devices’ 510(k) clearance. But the judge also moved to clarify for the jury the FDA’s role in the IVC filter’s market presence.

IVC Filter Makers Liability over FDA Process

The judge said that he would allow the FDA evidence “in context” and would not allow the 510(k) clearance to be used as evidence that the devices are approved by the FDA. (In Re: Bard IVC Filters Products Liability Litigation, MDL Docket No. 2641, No. 15-2641, Sherr-Una Booker v. C.R. Bard, Inc., et al., No. 16-474, D. Ariz., 2018 U.S. Dist.).

Bard loses $4.6 Million Verdict in First IVC Filter Trial

Having learned that the FDA had not approved the IVC filter but had only allowed it under the auspices of its 510(k) program may have helped sway the jury into seeing the problems caused by the product. The jury awarded the plaintiff $4 million, $3.6 million of which was assigned to C.R. Bard, maker of the IVC filter.

Related

- First Bard IVC Filter Verdict: $4 Million

- Bard IVC Filter Lawsuit

- Cook IVC Filter Attorney

- IVC Filter Use Decreases After FDA Advisory

by Matthews & Associates