Generic Drugs are not equivalent to Brand name drugs, according to the United States Supreme Court. Any person who takes a brand-name drug is protected by tort law. If a brand-name drug turns out to be more dangerous than advertised, or if its advertised benefits do not justify its risks – for whatever reason, including the drug maker’s concealing adverse events that it knew or should have known about – and the drug ends up injuring someone, then the person injured by that drug has recourse to sue the drug maker. The same cannot be said for generic drugs.

Generic Drugs are not equivalent to Brand name drugs, according to the United States Supreme Court. Any person who takes a brand-name drug is protected by tort law. If a brand-name drug turns out to be more dangerous than advertised, or if its advertised benefits do not justify its risks – for whatever reason, including the drug maker’s concealing adverse events that it knew or should have known about – and the drug ends up injuring someone, then the person injured by that drug has recourse to sue the drug maker. The same cannot be said for generic drugs.

Any person who takes a generic drug – and some 85 percent of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled by generic substitutions – has little to no chance of legally prosecuting that drug’s maker for her drug-induced injuries.

Generic Drug Victims dismissed by Supreme Court

This miscarriage of justice exists primarily because of two hotly-contested Supreme Court votes – both 5-4 – in favor of insulating generic drug makers from liability when they make a drug that injures or kills people.

The High Court revisits Orwell’s 1984

Though Congressman Henry Waxman, co-sponsor of the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 (the year’s Orwellian significance of which was not lost on the high court’s use of “Doublethink” in the relevant Pliva v. Mensing and Mutual Pharmaceutical v. Bartlett cases, in which a thing means its exact opposite, and one needs to turn logic on its head to ascertain the meaning of something), told the high court in an amicus brief that the intent of Congress and his and Hatch’s generic-drug-approval-streamlining bill was never meant to give generic drug makers a free pass or exempt them from tort law. Nevertheless, five on the Supreme Court in Mensing v. Pliva ignored Waxman, the AMA, the Constitutional Accountability Center, the U.S. Solicitor General, 100 years of Congressional presumption against preemption, common sense and decency, the simplest rule of human law (any entity making billions of dollars, as generic companies do, needs to be held responsible for its products) and voted to give generics a get-out-of-jail free card.

Orwellian Semantics

In a decidedly Orwellian display of semantics, the high court even used the Hatch-Waxman amendment as partial cover in a Neoliberal nod to the notion that making cheaper generics available was the be-all and the end-all, regardless of safety or responsibility. Here’s the doublethink: Five on the high court purport to be protecting the people by not protecting the people, by allowing corporations to police themselves. No other business in the world, save for those making bullets and bombs, gets to produce something that injures someone and yet pays no price for it.

Welcome to 1984. War is Peace. Love is Hate. Corporations are People (with rights that real people no longer enjoy).

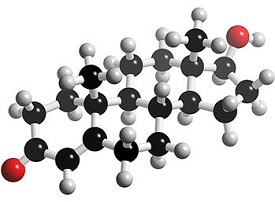

Generics fail True Equivalency Tests

The People’s Pharmacy reveals why generic drugs are not equivalent, at least why they are certainly not identical to the brand-name drugs they attempt to copy.

Many with a history of good results from brand name antibiotics reverse their results when they substitute a generic. Some generic antibiotics have been found to be ineffective for some antibiotic uses.

U.S. generic manufacturers must have a permit and approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to make and market drugs. A generic maker only needs to show the active ingredient is approximately the same as that of the brand maker. The determination of drug approval is made according to whether the generic drug is pharmaceutically equivalent, bio-available, and bioequivalent. These are all relative terms.

Generic Drugs are a Crapshoot

FDA only requires that one receives 80% to 125% of the drug into the bloodstream from a generic compared to the brand. Even more concerning, many different generic versions of the same drug exist, and each of these may also be different. If a generic only meets the minimum requirement and one refills that prescription with one that’s at the maximum limit, the potential increase in one’s body may be 45% percent higher, and one would have no way of knowing from the labels. The opposite could also obtain; one could be getting 45% less of the drug.

Pharmaceutical equivalence may be affected by many things, including inert ingredient variations and plants from different places. Plants can produce ingredients that greatly vary in quality, batch, manufacturing methods. Western Europe used to supply 80% of drug ingredients, according to a NY Times article April 11, 1996. Now, however, many ingredients come from plants in China, Japan, South Korea, India, Eastern Europe – where they are produced more cheaply. President of the National Association of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers, Bob Milanese, says that only a few of these plants meet FDA standards.He says it’s difficult to find people to inspect these plants. Another factor affecting generic quality is the international buy outs and diversification that allows odd combinations of questionable ingredients in generic production.

In addition, in oral drugs, capsule content may be over or under 7% of the stated content. And once a drug has been approved by FDA, manufacturers may make changes to the formula originally submitted.

Issues for the Elderly

Patient age can be a factor in pharmacokinetics – how the drug impacts the person. Digestive tract absorption of an oral drug can be altered by many factors, including higher gastric pH, accelerated gastric emptying, thinning and reduction of the absorptive surface. Bioavailability may be influenced by body fat, which can increase with age. It may be even higher in sedentary people. This increased fat to lean ratio results in a reservoir for lipid-soluble drugs which is larger, allowing those drugs to stay in the body longer, increasing the possibility of drug sensitivity by prolonging half-life. Conversely, water content declines with age, which means there’s a decreased volume of distribution for water-soluble drugs.

Bioavailability

Bioavailability relates to the drug’s effectiveness in terms of its absorption and the speed of that absorption. But pharmaceutically equivalent products can have different bioavailability. They may be absorbed faster or slower than the brand name drug, which may or may not be clinically significant.

The pH-dissolution profile of a product may be clinically relevant. Even if the coating is adequate to prevent release of the enzymes in the stomach where the ingredients are irreversibly inactivated, it may not dissolve after meals at the pH of the duodenum.

Bioequivalence

Bioequivalence studies examine whether drugs are functionally equivalent. The FDA requires an approved drug be effective within a 20% range of the original patented or brand name drug. This means effectiveness may be greater or less than 20% of the brand, so that two generics could be 40% different from one another. Therefore, a drug may be legally chemically equivalent (though Mensing and Bartlett clearly show us generics are not legally equivalent where it really counts) but not, at the same time, clinically equivalent. One study run on a generic of the anti-seizure medicine, Tegretol, found the generic allowed breakthrough seizures.

Other Generic Drug Issues

1) Some drugs lose potency on the shelf, so drug companies increase the strength in order that the aging drug will still provide a therapeutic level. Consequently, patients who use the drug soon after production when the dose may be stronger may be getting an overdose.

2) A generic substitution could result in a change in serum concentration.

3) Such a change may lead to significant adverse effects or loss of benefit.

4) The risk that patients may receive different generics each time they fill their prescription changes response to the drug.

5) Brand name cost is usually, but not always, higher than for a generic.

6) Blood tests can become necessary to determine adequate concentrations, excessive, possibly toxic concentrations or low, possibly ineffective concentrations

7) Time and effort spent adjusting the dose (if needed) can be costly.

8) Bioequivalence may be effected by the type of study. In one, two brand name pharmaceutical equivalents were each compared with a placebo in separate trials but were not compared with each other for bioequivalence. Though each was effective, it cannot be assumed that they produce the same clinical effect. Bioequivalence studies are performed on healthy volunteers and thus may not account for the full pharmacologic and therapeutic impact of generic substitution on patients with disease.

The bottom line is clear: Generic Drugs are not equivalent to the brand-name drugs they attempt to duplicate.

Related

- Generic Zofran not equivalent to Brand

by Matthews & Associates